Don't Fight About Your Feelings

Choose something more important

Here’s how the average fight goes.

“You hurt me.” “You hurt me too!” “Let’s fight until we feel better.”

Perhaps you, too, will stare at the above and think there’s something wrong.

It’s a rare fight that makes you feel better, at least in the short term. If you do feel better it’s usually not because of the act of fighting, it’s because of being heard, or getting new information, or having an insight about the world. Or because of the makeup sex.

Too often, fights are about resolving emotions. This is too ephemeral of a target. Fighting about feelings is like eating only for taste instead of nutrition: you’ll feel sick, and you’ll get fat from the fats and sugars and makeup emotions your body thinks it craves.

You’re looking for a specific taste instead of a specific outcome, and thus, only the high of the food (or the emotion) is where you’re getting fulfillment. 1% of the time, you get that Whopper of sweet, sweet anger, righteousness, sugar, and salt.

The other 99% of the time, you spend over the emotional toilet of your regrets.

This article will be about how to fight more effectively, more efficiently, and less emotionally. How to spend less time over an emotional toilet, and more time in connections that you love.

First, however, I need to give my usual amount of background. If you’re like “dude, enough with the science” go ahead and skip this next section. If you’re like “This is what I SUBSCRIBE for, bro!” then read on (after you…)

How Emotions Work When We’re Triggered

(A chunk of this section is cribbed from the manual for our upcoming course, The Art of Difficult Conversations. Credit to DasGeof for the initial research and writing.)

In my imagined sense of reality, my brain works something like this when I’m in conflict:

Trigger → Emotion → New information → Thought → New Emotion

In reality, brains work more like this:

Trigger → Emotion → New information → didn’t even hear it, still in the EMOTION → Sorry, didn’t know you were talking, still having an EMOTION

It takes a pause before the rest of the cycle can complete.

What’s happening in the brain that drives all thoughts away?

First, let’s meet our hypothalamus.

The hypothalamus is like the command center of our brains. It works in concert with the autonomic nervous system (ANS) to control involuntary bodily function like respiration, heart rate, and the release of chemicals like adrenaline.

In significant stress events, the amygdala (the emotional editorial room of the brain) calls into the hypothalamus. In milliseconds, long before we are consciously aware of what is happening, the hypothalamus is already sending out a body-wide emergency response message.

Now the body goes into overdrive. The hypothalamus sends signals to increase our heart rate, decrease blood pressure, dilate the pupils, increase respiration, and signal the adrenal glands to dump epinephrine into the bloodstream. Blood is drawn away from the GI tract, halting digestion. The excess oxygen is channeled primarily to the brain, heightening our senses and alertness. As epinephrine courses through the body, it also triggers the release of glucose and temporary fat deposits. Nutrients flood into a dilated bloodstream, resulting in a surge of energy throughout the body.

This entire chain activates before the visual and emotional centers of the brain process and make sense of what is actually happening. It’s that fast.

Now you’re all hyped up on the endogenic equivalent of cocaine, and, of course, that epinephrine is going to wear off and leave you with quite the hangover. So, the hypothalamus calls over to the pituitary and adrenal glands for a little extra help. If the threat continues beyond a few seconds they work in concert to maintain a constant flow of cortisol until the parasympathetic nervous system finally engages, ramping down the emergency response. The absence of all the chemicals makes you feel exhausted.

At this point, the amygdala has basically hijacked our frontal cortex. We are basically just reactive meat suits. We need to reboot, before we can focus on returning to anything resembling a rational discourse. And if you’ve ever been hyped up on cocaine, you know that either a single new piece of information or someone telling you to “calm down” is not going to get you off the ride.*

*There is a certain amount of firsthand research necessary for these articles. All for your benefit, of course.

In the Art of Difficult Conversations class, we present a couple simple and effective ways of calming ourselves down and activating our parasympathetic nervous system, such that we can reboot back to a regulated state. I’m not going to go into those here, because a) it’s not the point of this article, and b) you should take the class. Reading about regulation doesn’t actually help you practice it.

However, I will give one last factoid.

Alexithymia and Emotional Blindness

One hallmark of the trigger-state is the presence of alexithymia, an inability to identify emotions.

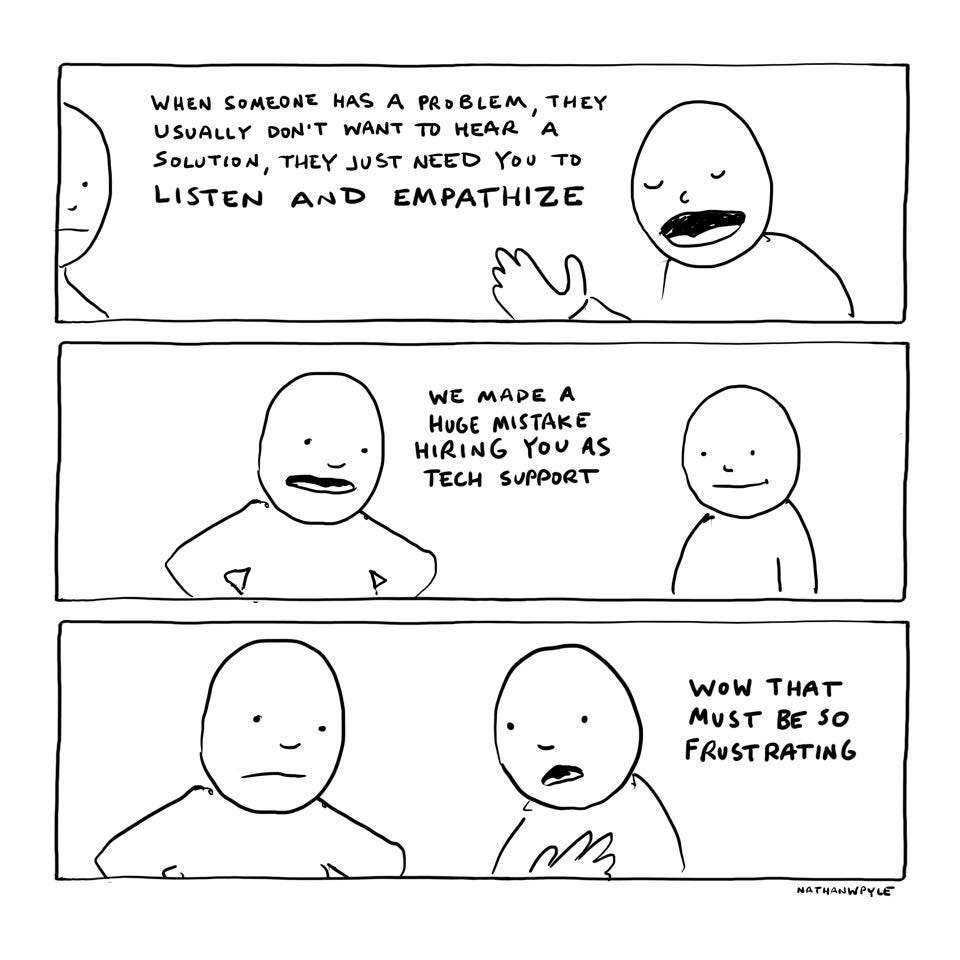

When we’re fighting about emotions, what we’re really fighting about is the fact of being emotional. We don’t have the ability to recognize nuances in our emotional state when we’re triggered. So we’re basically just yelling at each other, “I’M HURT!” “I’M HURT TOO!”

Without the ability to feel or name what emotions we’re trying to resolve, it’s even harder to fix them through fighting.

So What Do I Fight About?

Let’s return to our taste vs nutrition metaphor from the beginning. Fighting about feelings is like stuffing ourselves with fats, salt, and sugar. In the moment, we’re getting high. Our body is gorging on all those chemicals. It really doesn’t want to stop eating, because when it does, it will get withdrawal and exhaustion.

We can’t avoid feeding our bodies. Unless we’re on a strict and specific diet, some peaks and crashes are inevitable. Similarly, we can’t avoid all emotions in a fight.

But we can make our fights about something bigger than the emotions, just as we can make our meals about something more important than “The best, most addictive, most regrettable taste experience”.

We can make our meals about “feeling physically good” and “having energy to get through the day.”

We can make our fights about a bigger goal.

For example:

The last argument I had with one of my collaborators, call her Sofia, was about the priority of our work time. She wanted to focus a meeting on marketing. I wanted to focus it on content. We both have our areas of emphasis in the project we’re creating (a course on how to build successful in-person community!) and we sometimes clash about which should receive more air-time on any given meeting.

This conversation quickly spiraled. We started arguing about the past: what area we’d spent more time on already; how much each of us had dedicated to the project. I noticed myself becoming attached to feeling seen before I could end the fight.

Then, Sofia changed the game. She realized that a good goal for our argument could be to actually get clear on the topic at hand, and create a schedule for when we would work on marketing and when we would work on content. She pulled up a spreadsheet for us and started mapping.

To be honest, this was a wrenching shift for me without having the conversation resolved, but it got us out of the argument and solved our issue!

To see what I could have done differently and workshop a better goal than the one I had held, I played the scenario out in Fight Lab (a free weekly event we hold for conflict practice - join us for one!) this week.

I realized that in actuality, my goal in that argument - and that relationship - was to hold dignity more in conversations. My implicit goal is often to end our fights by backing down or pacifying, because I know we won’t get anywhere with our level of trigger. But I’ve started to avoid closeness with Sofia because of my fear of our conflicts, and I don’t like that.

Holding dignity might look like stating my view clearly, naming the dynamics at play in our interaction, and asking for a pause.

On our next fight, I’m going to hold that as my goal, instead of a vague desire to feel seen or get out as fast as possible. We’ll see what happens!

How to Focus on Goals Instead of Feelings

The TL;DR of this article is:

Don’t fight against feelings. Fight for goals.

To do this, we need to be clear on our goals. We can brainstorm these ahead of conversation, or take a step back in the moment and ask, “What do I want right now?”

There are 3 types of conversational goals:

Ones I hold for myself

Ones I hold for us

Ones I hold for you

Holding dignity in conversation is a self-goal. Calming us down enough to take a step away from the argument is an us-goal.

I do not recommend you-goals. These are where things get sticky, aside from fighting about feelings. If my goal is to change something in you, you will probably feel my desire for you to be different and react against it. And it’s unlikely that I’ll be able to really get you to change unless you choose that for yourself.

Much better for us to have an us-goal such as “exploring our patterns” or “Figuring out how to resolve this issue”.

Focusing on goals instead of feelings has been transformative for my fights.

How can YOU fight less about feelings, and more about something bigger, more concrete, and winnable?

Your Loving Thought-Dom,

Sara

P.S. This article talks about skills that we cover directly in our Art of Difficult Conversations course! I don’t love to do a lot of promo but I think these tools are important to learn in order to decrease our relational suffering. Thus, would love you to join us for the concrete practice.