The first course I ever created - that I can remember - was a series on how to circle, with my dear friend Jordan Allen, in November of 2014. Prior to that I’d created AR retreats, the Authentic Leadership Training, Circling events and immersions, and Games Nights; but I’d never made a several-week-long journey (the definition of a course).

Courses differ from a single class or a weekend-long event in that people have integration time in between. If taught skills, they have time to practice. If given connection, they need ways to continue it.

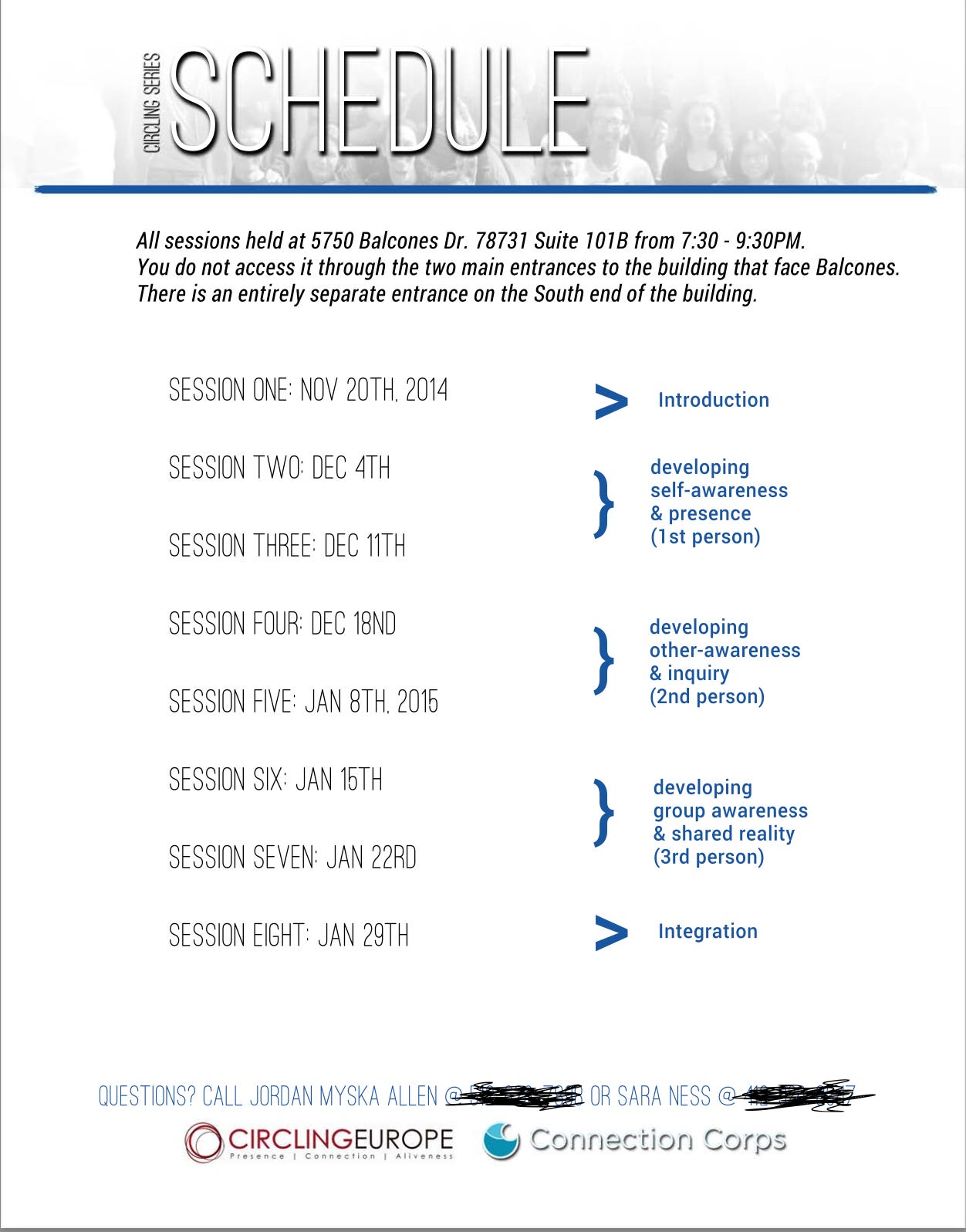

This is what the Circling series looked like:

What’s fun is that I would not teach this class much differently today. It was a good format for a relational course. We taught skills and played games for the first half, and then, for the second half, we circled. At the end of each class we debriefed the practice.

According to the learning theory I’ve read* and my own experience, this is the best way to teach individual skills:

Explain a single skill

Demonstrate it** or provide application examples

Provide a simple exercise to practice the skill

Give feedback (from instructor and/or peers)

Practice again

Debrief (for relational/rest purposes and/or for the instructor to offer corrections and suggestions)

Give a scenario that is relatively specific to each student’s life, or do the full practice, and have them use the skill within it

Give feedback

Practice again

Debrief

Give an application-based homework assignment, with a way to check in or followup on its completion (for example: accountability buddies, or the Changemaster 3000 journal we used to assign to Authentic Life Course students)

*Note here: I usually research original sources for these articles, but all the articles I found on learning theory, at first glance, were subjective or philosophical instead of studied results. Which explains something about the wildly varying effectiveness of teaching practices. The model I share here is, instead, based on something I read in Crucial Influence, a book whose conclusions tend to be based in a lot of practice and research. I chose the model because it holds most true to my own experience in teaching. But also modified it wildly here 😂

** I sometimes skip this step, personally. For more subjective skills, doing a demo can influence students towards a particular form of the practice - they will, always, base what they do on the possibilities they saw - so I’ll often have them do the practice first, report back, then perhaps provide several demonstrations or examples afterwards. This is, btw, the main reason we have multiple leads and mentees of different leadership styles on all of our courses: multiple models help students not attach to any one form. Or that’s my theory, anyways.

Here is the way I tend to fuck this up:

If you haven’t already figured this out from my articles, I like to give information. A lot of information. Some (okay, basically everyone) might say too much information. This is probably because a) I love the phase of gathering and sorting information and want to always do more of it, and b) I want to teach the full topic and all the skills around it - which, with the wide topics I teach, like “how to facilitate” and “how to have difficult conversations”, is a stupid proposition.

This creates two problems.

First, my courses don’t just explain a single skill each class. They explain several skills.

Second, each class doesn’t have enough time for the students to follow the full process. Usually we get to a single skill-based exercise with feedback and a debrief. We don’t get a second practice of the skill, or the application of the skill to a real-life situation.

We are working on changing this in our courses. For instance, below is the class plan for our most recent round of the Art of Difficult Conversations:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sara’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.