Part 1 of this series explained the history of Contact Theory, and its effectiveness as a tool for reducing intergroup and individual prejudice. Part 2 will focus on how to use the tool….

Imagine this scenario. You, a white man, end up in an elevator with two black women (feel free to switch the races and genders to fit your experience; any disparity will work here). The elevator dings; you get off. Have your attitudes to the other race or gender changed?

No, probably not; not even if you talked for a couple of minutes. Simple contact does not create change.

Inhabit the scenario again. You’re in the elevator, and all of a sudden the lights go out. The elevator is stuck. You’re in there for minutes, then for an hour. You can’t call for help - the button isn’t working, and your phones don’t work between floors.

You begin to brainstorm with the other people in the elevator. Each of you comes up with ideas of what to do: remove the top panel and climb into the shaft? You don’t know if the movies are right and there are actually ladders up there; plus, none of you is in good enough shape to jump. Wait it out? It’s already been several hours, and you’re having a hard time staying calm.

Eventually, you all decide to force open the elevator doors and see if you can jump down to the landing of the next floor. You and another person get your fingers into the doors and pull. It comes open!

You’re only a few feet above the next floor. You pull down the interlock holding the shaft door closed, open the door, and jump down. Each of you helps the others to land and get out safely.

Once you’re out of the elevator, you cheer and give each other high fives, and even hugs. Who’d have known that you would hug a stranger, let alone one of such a different form, just a few hours before?

You part ways. But, every time you see each other in the halls after that, you give big smiles and waves. You’ve been through something together. Perhaps, you even treat your co-workers of that race and gender a little differently.

Or do you?

The Conditions for Change

It’s obvious that the second elevator situation creates more bonding than the first. It’s more time together, more intensity, more interaction. But what I care about is whether that bonding is transferrable. If these people bond, are they nicer in general to others? Do they see the out-group to which the other elevator members belong as more acceptable? Does conflict, worldwide, go down just a bit?

According to Science™, the answer is: “Yes, under certain conditions”. Here’s how Gordon Allport, the father of Contact Theory, thought about it.

There are 4 conditions that bring about positive intergroup interactions, to the point where prejudice (and thus long-term conflict) can be reduced. As Gordon says,

“To be maximally effective, contact and acquaintance programs should lead to a sense of equality in social status, should occur in ordinary purposeful pursuits, avoid artificiality, and if possible enjoy the sanction of the community in which they occur. The deeper and more genuine the association, the greater its effect.

While it may help somewhat to place members of different ethnic groups side by side on a job, the gain is greater if these members regard themselves as part of a team.”

(There is high statistical support for this theory, btw - one meta-analysis, by Pettigrew and Tropp (2000) looked at 203 studies involving over 90,000 participants. They found that Allport’s conditions were significantly related to decreased intergroup biases, both for majority and minority participants.)

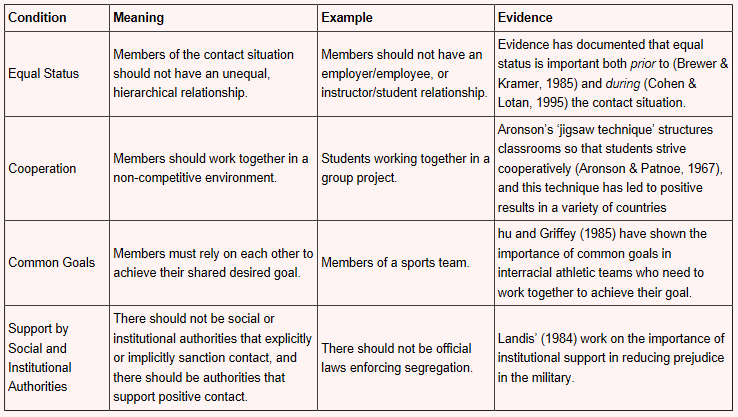

These factors break down into:

Future research showed that these conditions are both jointly and independently useful. I.e. if you have common goals but not fully equal status, for instance, you can still get positive effect.

I’ll go through all of these. But having read through the research, I posit that this list should be changed a bit. To me, the most important factors that have been discovered and proven in the years since seem to be

Equal status

Cooperation on common goals

External support

Ongoing connection

Let’s get into it.

Equal Status

Let’s say that, in the elevator situation, one person had taken control. They began leading the group, solving the problem, and guiding everyone else to safety. Although this would be effective for getting you out of the elevator, it would not be as effective for decreasing prejudice and increasing connection between group members. Equal status and authority = better contact outcomes.

Adherence to the Rule

Google’s Project Aristotle is my favorite example of this norm. Google studied hundreds of teams across their organization to understand why some were more effective than others. After years of research, they realized that the impactful factors had to do not with demographics, experience, or compensation - they had to do with interpersonal dynamics. Specifically, two factors that added up to something called “psychological safety”.

Here’s an article I wrote on that a few years ago, if you want to learn more. (I’ve also done some good workshops on it for large companies - it’s a fascinating topic, and one of the best pieces of research to support the value of communication practices like Authentic Relating).

The highest defining factors of team success, leading to psychological safety, were:

Safety of discussion: that each member of the group spoke a relatively equal amount

Social sensitivity: that team members noticed and responded to each other’s emotional states.

This first point, equality of conversational turn-taking, is a great guidepost for equal status. And it takes maintenance. The best-performing teams at Google did things like intentionally stopping team members from interrupting each other. As a result, they gained respect for each other, and respect led to higher performance. Turns out, it can also decrease prejudice.

Disloyalty to the Rule

There is a term in business consulting called a HPPO (pronounced “hippo”).

The HPPO is the “Highest Paid Person’s Opinion”. When we talk about this, we usually mention it in the form of “How do we get the HPPOs out of the room?”

Something I’ve found, being a leader and a CEO for many years, is that even if I don’t notice it, my opinion has more weight than others among those I lead. This is very subtle, y’all: if you’re in power, you just won’t see it. It’s not anything you’re doing. It’s the natural human tendency to follow, which we ourselves do when others lead. It’s the bystander effect, where if we think someone else has something covered, we don’t pick it up.

If you’re trying to create a positive contact situation, and you let a HPPO - or similarly powered individual - dominate, then everybody else won’t take as much responsibility for their own experience. They will hear, but not listen; they will follow, but not change.

Application of the Rule

“Sara”, I hear you say, “This is all well and good, and I appreciate how much research you put in to prove things that are relatively self-evident. But how do I USE this?”

Let’s imagine that you are bringing together police officers and African Americans for a workshop, and you want to equalize status. You might:

Make sure that the police chief is matched with higher-status members of the black group for exercises and conversations

Have the highest-authority and -status members only contribute to group discussions at the end, after they’ve witnessed everyone else speak

Give the group a task like “work on how to decrease gang violence leading to high incarceration rates” (something that both groups would probably care about, if worded correctly) where every member has to come up with ideas independently, then present them to the group, and there is a norm of no interrupting or shooting down others’ ideas.

For discussion, instead of standing for their own idea, group members can only speak to why they think one of the other side’s ideas could have value.

Would these work? Not sure, I haven’t tried them all. I have used the first two when hosting company workshops, where authority differentials are highest - for instance, when holding Listening Circles for companies in crisis, I coach the executives to only speak at the very end, and it works great for encouraging honesty among the employees.

If you try these, let me know :)

Let’s move on to the second Condition for Change.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sara’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.