The Women's Group Guide, Part 5: How Things Fall Apart

In which we battle and befriend entropy

This is the last article in my series on “How to Start a Women’s Group”.

Before we get started, a little shout out to all the readers who have NO interest in starting a women’s group, but have stuck around as subscribers for the last few weeks: Thank you. I appreciate your support. I do believe community is one of the most useful things we can found in this age of uncertainty, and I hope you’ll be able to use this content to form other kinds of affinity groups, whether it be with parents or colleagues or the neurospicy. Either way - you’re the best.

This last article will apply not just to women’s groups, but to anyone who has ever founded a lovely group and then attempted to keep it going. To cite a graphic I made for an article long ago:

Creating community is hard. It’s rewarding, sure. But trying to get a bunch of people to go any one direction together is like attempting to lure an entire pack of cats with a laser pointer. Their attention only lasts so long; you have to keep re-engaging them, or finding more interesting lasers. And when they get bored or annoyed they’ll scratch the most obvious person there: you.

But, as Thich Nhat Hahn said: “No mud, no lotus.” We don’t get the beauty without the difficulty. Every group must go through tough times. These can tear us apart, but they can also make us stronger.

Let’s look at how.

I’ll start with a story.

The Death of the Lacuna Ladies

For about two and a half years, my women’s group, Lacuna, was a core part of my life. We held 4-day retreats once a season, plus monthly “in-betweenies”. We saw each other through COVID, breakups, a marriage, and the death of Carrie’s daughter - my god-daughter - Bianca. One retreat, Carrie and I traded off between coming and looking after B in the hospital.

To me, the group felt like family. So it was immensely painful for me when it ended, and for many years, I asked myself if there was something I could have done.

I think there was.

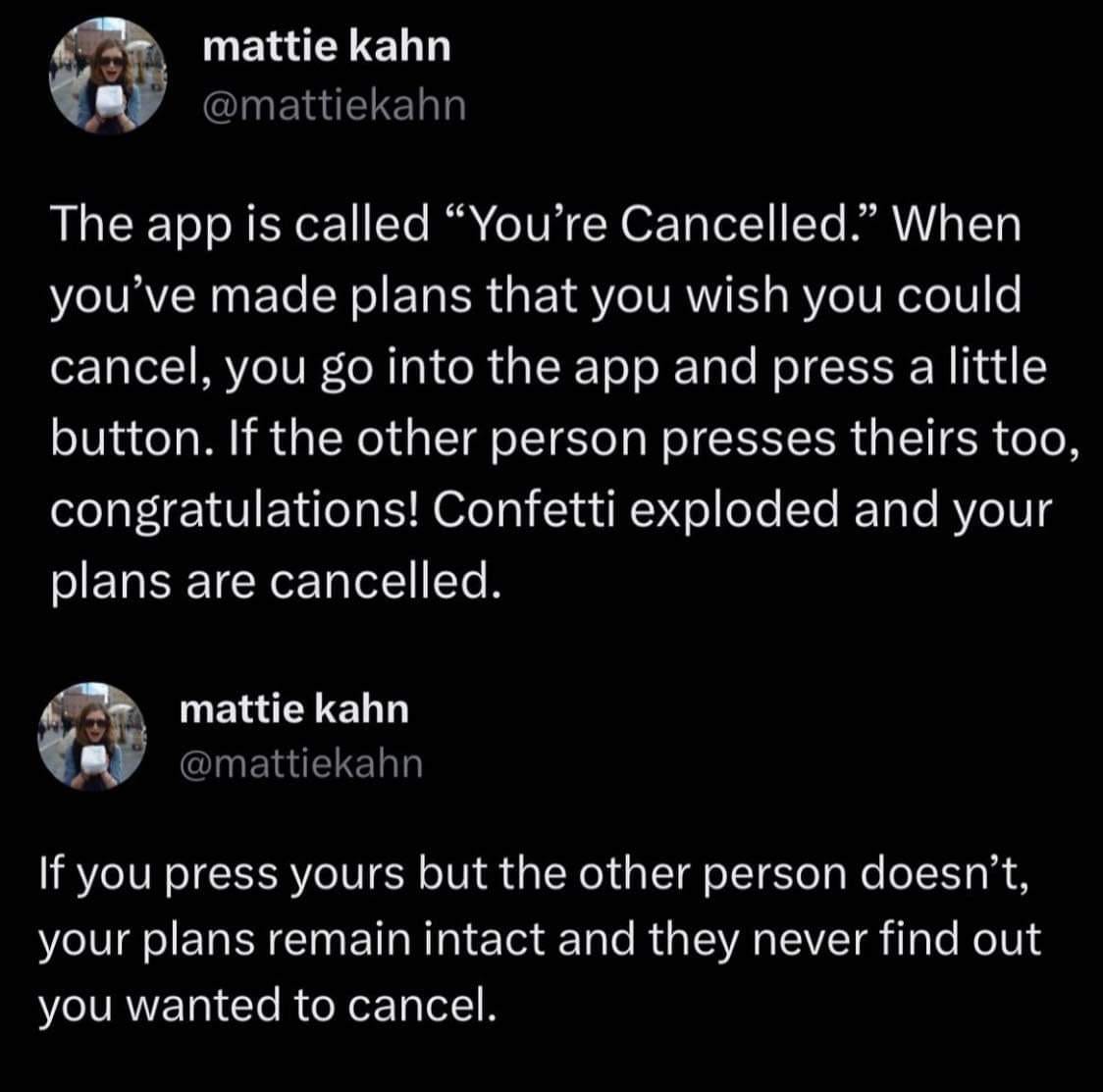

The group ended slowly. There was no big discussion, no big breakup. What happened was: one woman began dropping out before events. Not withdrawing from the group - just messaging our thread, a few days before a retreat or in-betweenie, naming her deepest apologies, but [some life event] was taking priority over group time.

The thing about groups (especially womens’ groups) is: once one person drops, everyone else starts contemplating what else they could be doing with their weekend. Most people don’t drop because they have other plans; they drop because they want time alone. Every time, once we get to a retreat, we feel so grateful to have the connection. But anticipating the trouble - the energy it takes to break that membrane of travel, settling in, and being vulnerable with those we love - when one person gives us a way towards greater comfort, we start contemplating: “Wouldn’t it be nice to just stay home and watch a show?”

(Side note here: in Robert Putnam’s amazing book Bowing Alone, he examines the factors contributing to America’s decline in social connection, which began in the late 1960s. The book has some amazing statistics, and considers factors from women joining the workforce to urban sprawl to time and money pressures. All in all, after he controls for an astonishing variety of possibilities, the greatest chunk of the decline - about 25% - is attributable to TV. Being able to stay in the comfort of our own home and watch other people interacting in scripted ways, to feel as if we’re socially connected even when we’re not, and to be passively entertained: this turns out to be a great way to trick our souls into feeling satisfied.

If you want one life hack for being more connected? Turn off the TV. Believe me, you’ll soon be bored enough to make friends.)

Once this woman dropped, others would find reasons they couldn’t be there. One retreat, three ladies dropped out within 48 hours of the start, leaving the other four of us to have a weekend together in a giant half-empty Airbnb. We still had fun, but it was the death knell of our group.

Finally, we had a group conversation to confirm the inevitable: our group was over.

I was devastated. I didn’t understand. To me, this was family. We had seen each other through massive life events; we had been each other’s closest confidants. How could it just end?

Now, two years on, I can (maybe) see what happened. Group factors are always complex, so perhaps these interventions wouldn’t have fixed the problem. But I like to think they would have helped.

First of all:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sara’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.